The Assam School of Painting

With the rise of Neo Vaisnavism under Sankaradeva, from 16th century onwards, we get a host of concrete examples that can be called painting in its real sense, that flourished until the last part of the 19th century. These polychrome paintings, popularly known as manuscript painting, done on sanchipat or tulapat, which also contained written descriptions, have certain independent characteristics of their own and are collectively grouped as The Assam School of Painting. Since it was the Satra institution of Sankaradeva which nurtured this school and played a considerable part in its growth, preservation and popularity, the Assam School may also be referred to as the Satriyā School of Painting.

With the rise of Neo Vaisnavism under Sankaradeva, from 16th century onwards, we get a host of concrete examples that can be called painting in its real sense, that flourished until the last part of the 19th century. These polychrome paintings, popularly known as manuscript painting, done on sanchipat or tulapat, which also contained written descriptions, have certain independent characteristics of their own and are collectively grouped as The Assam School of Painting. Since it was the Satra institution of Sankaradeva which nurtured this school and played a considerable part in its growth, preservation and popularity, the Assam School may also be referred to as the Satriyā School of Painting.

“The impulse to create the art of painting can be explained by the evolution of the worship of religious scripture. The worship of scripture in the altar of each Satra enjoyed unprecedented impetus. The practice was also followed in the domestic chapel of each and every household in Assam. The reason behind the phenomenal growth of (painted) religious transcripts in innumerable number can alone be attributed to this practice.”

At least one hundred manuscripts belonging to the Assam School, which are “painting in its real sense”, have been discovered so far, each manuscript containing, on an average, forty such polychrome paintings. The art of painting in Assam flourished from the Sankari period (15 th - 16 th century AD) until the last part of the 19 th century.

The Guru showeth the way..

From the caritas, it is found that Sankaradeva was also a master painter possessing extensive knowledge about the nuances and aesthetics of the art of book illustration and painting. After he had finished writing his celebrated Gunamala, the Guru painted on tulāpāt, with vermillion and yellow arsenic, the picture of an elephant, and pasted it on the wooden book case in which the manuscript was placed. This he did apparently to depict with the paint-brush the metaphor of 'elephant in a pot'. On another occasion, he is said to have painted the sapta Vaikuntha (the seven Vaikunthas) on tulāpāt. Thus, it was the benign touch of the Guru which showed the way to the future artists of the Assam School of Painting.

Exceptional Artists

Primarily due to the emergence of Sankaradeva's religion, a vibrant cottage industry came into being and there were distinct communities - the khanikars, the Likhaks and the Patuās - whose subsidiary means of livelihood was the transcription and illustration of manuscripts. Working under the guidance of the Vaisnava preachers, these artists inaugurated the Assam School of Painting. The Satras used to patronize and support the khanikarsIn Assam, the painter was known by the most popular name khanikar although a khanikar could be a sculptor, an engraver, a carpenter, a maker of earthen images, a painter, etc. The principal duty of this professional group was to paint, make images, etc. The village khanikar enjoyed an important position in the cultural life of the people. Without him, no bhāwnā or theatricals could be imagined. For, he not only painted the scenes and sets but also dressed the actors and designed their costumes and accessories. Masks or mukhās were also made by him for superhuman roles like that of Hanumāna. “He had derived his inspiration from and perfected his skill in the arts from an accumulated fund of hereditary knowledge.” to work with their penmanship.

Primarily due to the emergence of Sankaradeva's religion, a vibrant cottage industry came into being and there were distinct communities - the khanikars, the Likhaks and the Patuās - whose subsidiary means of livelihood was the transcription and illustration of manuscripts. Working under the guidance of the Vaisnava preachers, these artists inaugurated the Assam School of Painting. The Satras used to patronize and support the khanikarsIn Assam, the painter was known by the most popular name khanikar although a khanikar could be a sculptor, an engraver, a carpenter, a maker of earthen images, a painter, etc. The principal duty of this professional group was to paint, make images, etc. The village khanikar enjoyed an important position in the cultural life of the people. Without him, no bhāwnā or theatricals could be imagined. For, he not only painted the scenes and sets but also dressed the actors and designed their costumes and accessories. Masks or mukhās were also made by him for superhuman roles like that of Hanumāna. “He had derived his inspiration from and perfected his skill in the arts from an accumulated fund of hereditary knowledge.” to work with their penmanship.

The skilled and artistic penmanship of the scribes was so much on demand that one scribe usually specialized in the copying of one particular book instead of becoming a free-lancer in his profession. The skill of a painter was generally requisitioned to decorate the labors of penmanship. The scribe was sometimes a painter himself and, if not, a regular painter supplemented the work of the transcriber by sketches on spaces left vacant for that purpose.

The Subjects of the Paintings

The stories of the Bhagavata, the Puranas, the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and the epics were generally illustrated. When pictures could not be inserted, illuminated margins occasionally made up the deficiency. Manuscripts with illustrated borders were known as latā-katā puthi or manuscripts with scrolls and running motifs along the borders. Many manuscripts contain pictures of the deadly sins, of the glory of Visnu, and of His incarnations according to Hindu conception.

The stories of the Bhagavata, the Puranas, the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and the epics were generally illustrated. When pictures could not be inserted, illuminated margins occasionally made up the deficiency. Manuscripts with illustrated borders were known as latā-katā puthi or manuscripts with scrolls and running motifs along the borders. Many manuscripts contain pictures of the deadly sins, of the glory of Visnu, and of His incarnations according to Hindu conception.

Pictures of Sankaradeva sitting in a siksha-mudra posture and surrounded by his apostles are met with occasionally in his biographies eg, in the Vanamālidevar Carita and on the obverse of the first folio of the Guru Carit Kathā, collected by the famous scholar Bani Kanta Kakati and deposited in the manuscript section of the Gauhati University. Rajatananda Dasgupta of the Benares Hindu University gives an appraisal of this picture as a “great leap forward in portrait painting.”

The Materials Used in Painting

All combinations of colors were used. The prominent ones were yellow and green.

The materials used in painting are :

- indigo

- yellow ochre (geru māti)

- hengul (vermillion) one of the chief components used

- hāitāl (yellow arsenic) also one of the chief components

- lamp-black

These materials could easily give the basic colors and even a few composite ones. The use of a crude variety of chalk (dhal) sometimes in the preparation of the painting surface in many cases accounts for the decay of the color of, and sometimes the paintings themselves

These materials could easily give the basic colors and even a few composite ones. The use of a crude variety of chalk (dhal) sometimes in the preparation of the painting surface in many cases accounts for the decay of the color of, and sometimes the paintings themselves

Famous Painted Manuscripts

The Earliest Surviving Specimen

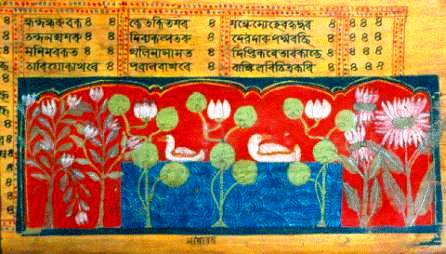

The earliest extant example of an illustrated manuscript of the Satriyā school is the Bhāgavata Book X (Dasama) (the Citra Bhāgavata) from the Bāli Satra of the Nagāon district. It is dated as 1539 AD. Though sharing some common features with the western India miniatures, it has an independent identity and Dr Moti Chandra lays down the following distinctive features of the said manuscript:

The earliest extant example of an illustrated manuscript of the Satriyā school is the Bhāgavata Book X (Dasama) (the Citra Bhāgavata) from the Bāli Satra of the Nagāon district. It is dated as 1539 AD. Though sharing some common features with the western India miniatures, it has an independent identity and Dr Moti Chandra lays down the following distinctive features of the said manuscript:

- lyrical draughtsmanship

- simple composition

- dramatic narration

- splendid color

These elements “give the Bhāgavata illustrations a charm which distinguishes them from similar Bhāgavata paintings from Udaipur and elsewhere.”

Many more illustrated manuscripts covering three centuries including the 19th century have been recovered from different Satras and households of Assam during last seventy years or so. Although the pictorial idiom by and large remains the same with all these works, there are stylistic variations among the artists mainly due to individual comprehension of the text and the ability of the artist in matching the verbal imagery through a parallel pictorial imagery.

The Citra Bhāgavata was followed by the execution of the illustrated Bar Kirttana of Kāthbāpu Satra, the Bhakti Ratnāvali executed in 1683 in Kamalābāri Satra, the Gita Govinda and the Ananda Lahari seem to have rendered by a sattriyā artist in the Ahom court of Rudra Singha (1695-1713 A.D.) and Siva Singha (1713-1744 A.D) (the Ananda-Lahari can be more precisely placed during 1720 A.D. and 1721 A.D), the Ajamilopākhyāna of Puranā Burkā Satra, the Bhāgavata VIII of Pubthariā, the Bhakti Ratnāvali of Ratnāvali-Thān in Nagāon and the dated copy of the third transcript of the Bhakti -Ratnāvali (1731 A.D) of Karatipār NaSatra in Nagaon . The artist of Bengenā-āti-Satra in Mājuli rendered paintings in the folios of the Sundarakānda Rāmāyana in 1715 A.D. In the same year, Visnurāma of Chalihā-Bāreghar Satra executed the paintings of the Ajamilopākhyāna Nāt written by the Satrādhikara, Srirāmadeva of the said Satra. Excluding the Bar-Kirttana, Sundarakānda, Ajamilopākhyāna Nāt, the other seven illustrated manuscripts stated above are stylistically similar and constitute one group from stylistic consideration.

One of the major contributions to the art of painting in Assam was the Lava Kusar Yuddha. The manuscript is undated. Its pictorial style is developed better than that of the Citra Bhāgavata and those executed between 1683 and 1732 A.D.

In 1836 the Ahom prince, Purandar Singha, whom the British company placed on the throne for a very short period after the fall of the Ahom kingdom during the Burmese aggression, commissioned the services of one Durgārām Betha for illumination work in the folios of the Brahmavaivarta Purāna (now in the British Library, London). It was a masterpiece of the 19th century. According to J.P. Losty, “this is the last of the great ones, in which the native Assamese style has triumphantly reasserted itself over the desiccated Ahom court style.”

Distinguishing features

The general composition and layout of the paintings are always horizontal as opposed to the vertical way of contemporary Persia, and Europe. Each painting is divided into two major sections. The background proper is always monochrome red free of any details. The rest of the 'ālekhya-sthāna' is painted in flat green on which the actual painting appears superimposed. The most characteristic feature of these miniatures is that each human, animal or any other figure is framed by trifoil arches or 'architectural niches'. As a result, the top portion of the background is always of irregular shape, following the contour of the arch or series of arches if the panel is a longer one. The entire area is never broken into foreground, background or horizon, either by changes in their respective colors or by the introduction of symbolic and significant motifs like grass, plants or clouds. The entire composition appears to be in eye level view, all other perspectives being absent here.

The general composition and layout of the paintings are always horizontal as opposed to the vertical way of contemporary Persia, and Europe. Each painting is divided into two major sections. The background proper is always monochrome red free of any details. The rest of the 'ālekhya-sthāna' is painted in flat green on which the actual painting appears superimposed. The most characteristic feature of these miniatures is that each human, animal or any other figure is framed by trifoil arches or 'architectural niches'. As a result, the top portion of the background is always of irregular shape, following the contour of the arch or series of arches if the panel is a longer one. The entire area is never broken into foreground, background or horizon, either by changes in their respective colors or by the introduction of symbolic and significant motifs like grass, plants or clouds. The entire composition appears to be in eye level view, all other perspectives being absent here.

Representations of pouring rain water, rivers and lakes are of a conventional type. Mountains (for example) look like cross sections of them as in a geological diagram. The lack of expression in the faces of human figures are simply compensated by their poses and mudrās which are greatly effective. They are all in 'Abhanga', a few in 'Tribhanga' and almost none in 'Atibhanga' poses. In depicting an episode, parts of it are represented on the succeeding folios. But the technique of continued narration is also followed at times. No attempt to depict the sky in a realistic manner is perceptible. Where figures are inserted the background is invariably red but the area between the red background and the rest of the the alekhya-sthana is usually painted in equally flat monochrome green.

Representations of pouring rain water, rivers and lakes are of a conventional type. Mountains (for example) look like cross sections of them as in a geological diagram. The lack of expression in the faces of human figures are simply compensated by their poses and mudrās which are greatly effective. They are all in 'Abhanga', a few in 'Tribhanga' and almost none in 'Atibhanga' poses. In depicting an episode, parts of it are represented on the succeeding folios. But the technique of continued narration is also followed at times. No attempt to depict the sky in a realistic manner is perceptible. Where figures are inserted the background is invariably red but the area between the red background and the rest of the the alekhya-sthana is usually painted in equally flat monochrome green.

Vegetation though stylised is varied and the Kadamba, the Banana and other willowy trees with flowers are the most common types represented. The usual practice is to fill the crown area in some kind of green and then the leaves and the flowers are picked out in minute details. Cuckoos and other harmless beasts and birds inhabit these trees.

Human figures and superhuman beings in anthropomorphic forms are all characteristic of the school. In the case of human figures, natural proportions are adhered to but, when, in particular episodes Krishna's personality had to be magnified he is shown far larger in size.

The last days of the Satriyā school were marked by minuteness of details, lavishness of ornamentation and gorgeousness of colors.

Influence on Later (Sub) Schools

The Satriyā school later had many branches and offshoots and new schools came into view but these other schools were deeply influenced by and/or penetrated by ideas and techniques of the Satriyā school - the school that Sankaradeva had launched.